UNSW Environmental Scientist and science student Jieyu Liu visited Sarah Jane’s studio for the first time in July. Sarah Jane wanted to interview Jieyu in order to gain an understanding of her interface with the Sydney Rock Oyster. Together they wrote this blog ‘Tales from an Environmental Scientist and Sydney Oyster Girl’.

Jieyu brought her first paper back full of carefully cleaned oyster shells in a brown paper bag. It was May and the sun was shining and the shells were handed over like an offering. I was excited. The first donated shells of the project! I was thrilled. I peered in the crumpled bag and carried them to my studio. I laid them out on the bench. I played with them, I made patterns with them and imagined them as carriers fo stories. The oysters had made a journey to me across Sydney. They were a remnant of a celebration, a get together. I imagined the folk that had had eaten them, the hands that had touched them and tracked back, back to the hands that had grown and harvested them. There were many hands. I wanted to harvest the stories of these shells, to mine the connections, to drill down into the reefs, the communities the peoples who consumed them, who cherished them, whose slithery and slippery slide journeyed to me. To my hands. Like a modern midden, the shells are mounting. I like the complexities and the stories associated with their journey to me.

The second time that Jieyu offers up her shells to the project there are hundreds! I am overwhelmed. They make a wonderful sound when Jieyu pours them in and through my open hands. I scurry to my studio. I wash. Sort. Clean. File.

I take a few home in my hand bag. On the way home, I reach down and into my bag to hold one. I make it warm. I give it new life. I carry it with me like a scar.

I wait for Jieyu; for the offerings, the shells.

I wait for her, my oyster girl.

I wait.

SJM

My name is Jieyu Liu, and I am an honours student in the Ferrari Lab from BABS school, UNSW. I am currently working on a bioremediation project at Casey station with Australian Antarctic Division. I got to know Sarah Jane through Sally Crane, one of Ph.D candidates from the Ferrari lab. Sally is a member of the BEES and BABS Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Committee at UNSW and a passionate supporter of the arts and Sally let me know that Sarah Jane had gained funding to work with an Indigenous scientist and make art works using the Baludarri or Sydney Rock Oyster as a main theme. She let me know that Sarah Jane was trying to find people in the UNSW committee to co create oyster stories with her.

Outside of the lab, I work as a part-time oyster shucker in a company called Sydney Oyster Girls. In the seafood industry, Sydney rock oysters are the icons of Australia.

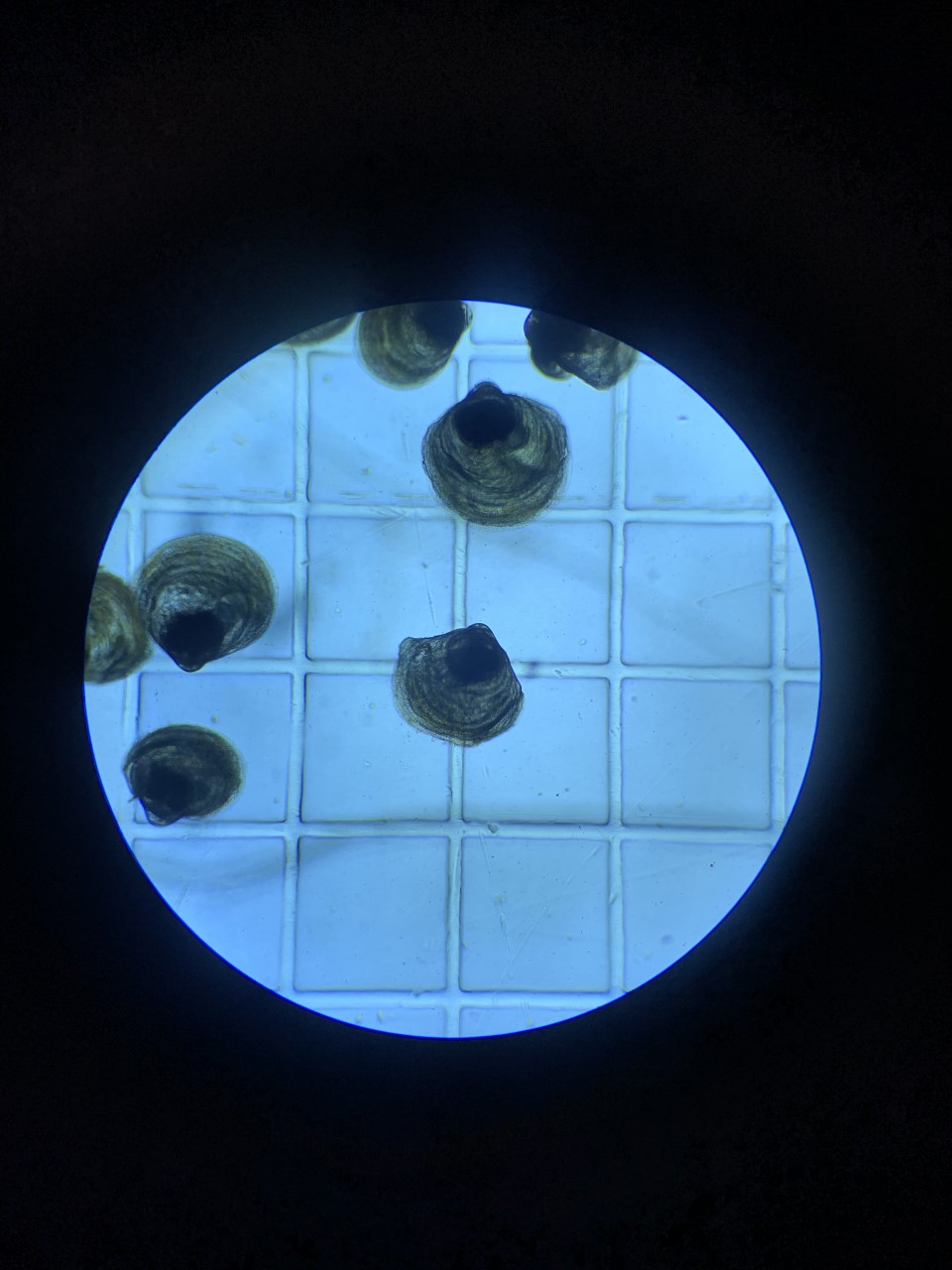

After learning that Dr. Moore was collecting Sydney Rock Oyster Shells for her art project, I sent her an email to her. I reached out and offered to help her with her art making through collecting the precious oyster shells and bringing them to her at the university. I emailed her and she immediately replied back with some pictures of her amazing art work. Her art work was made with oyster shells and she shared with me that she was working with an Indigenous scientist whose experiments were assisting knowledges about future proofing the Baludarri. I heard that there were many ancient stories about Sydney oysters and from then, I started collecting leftover oyster shells from my hospitality work.

Today, I was invited by Sarah Jane to her oyster studio, which is located in BEES school. As an environmental science student and an oyster lover, I can’t tell you all how happy I am when I see these food “waste” became a part of art that she has made.

From the perspective of my customers, fresh Sydney Rock Oysters are regarded as a luxury. I shuck them in five seconds. Once I open the shell they are still alive and I can’t see them moving. It looks beautiful. The meat is a creamy colour. If it is alive it will be juicy. After I shuck them I cut off the large muscle that connects it to the shell and I flip the meat around so ti shows the plumpest part of the oyster to the customer. I shuck 100 oysters in an hour. I use an oyster shucking sharp knife with a short blade. I squeeze a halved lemon onto the oyster meat and then I serve them. I serve them direct to the customer on a napkin. Some people don’t take a napkin but take the shells in their cupped hand. I giver them the oyster and they slurp it usually in one swallow.

Th customers say to me ‘It tastes beautiful’. They say ‘It tastes so fresh’. Some of the customers, particularly the children do not like the taste and they spit in into the napkin.

Before I met Sarah Jane I thought of the shells as rubbish now I know that they are really valuable and truly beautiful.

Before I moved to Sydney in 2015 I had never tasted an oyster. I am from China and I am from a small inland city. We have rivers but no oysters. I tasted my first oyster in 2018 on my first shift at work. I am now totally hooked. I can eat a dozen oysters in one sitting. I love them. Especially Sydney Rock. They are beautiful. I have tried the Pacific Ocean oysters. They are much bigger, They are huge. They can be as big as my hand but they are not as soft in texture as the Baludarri.

I like my job. It connects me to the people of Sydney. I help people celebrate with the people they love. It is connecting.

Jieyu Liu, July, 2019