I will be facilitating a Baludarri Reef Making Project during the UNSW Sydney 2019 Diversity Fest that will run over 5 days from Monday 23rd of September to Friday 27th. The reef building will take place each day between 11.30-1.30 for the length of the festival and everyone is welcome to join in!

Each day of the festival a team of volunteers and I will set up in the Quad and the project involves straw bales, Shoalhaven river mud, oyster shells, clay, imagination, creativity and play.

What does the building the reef project involve?

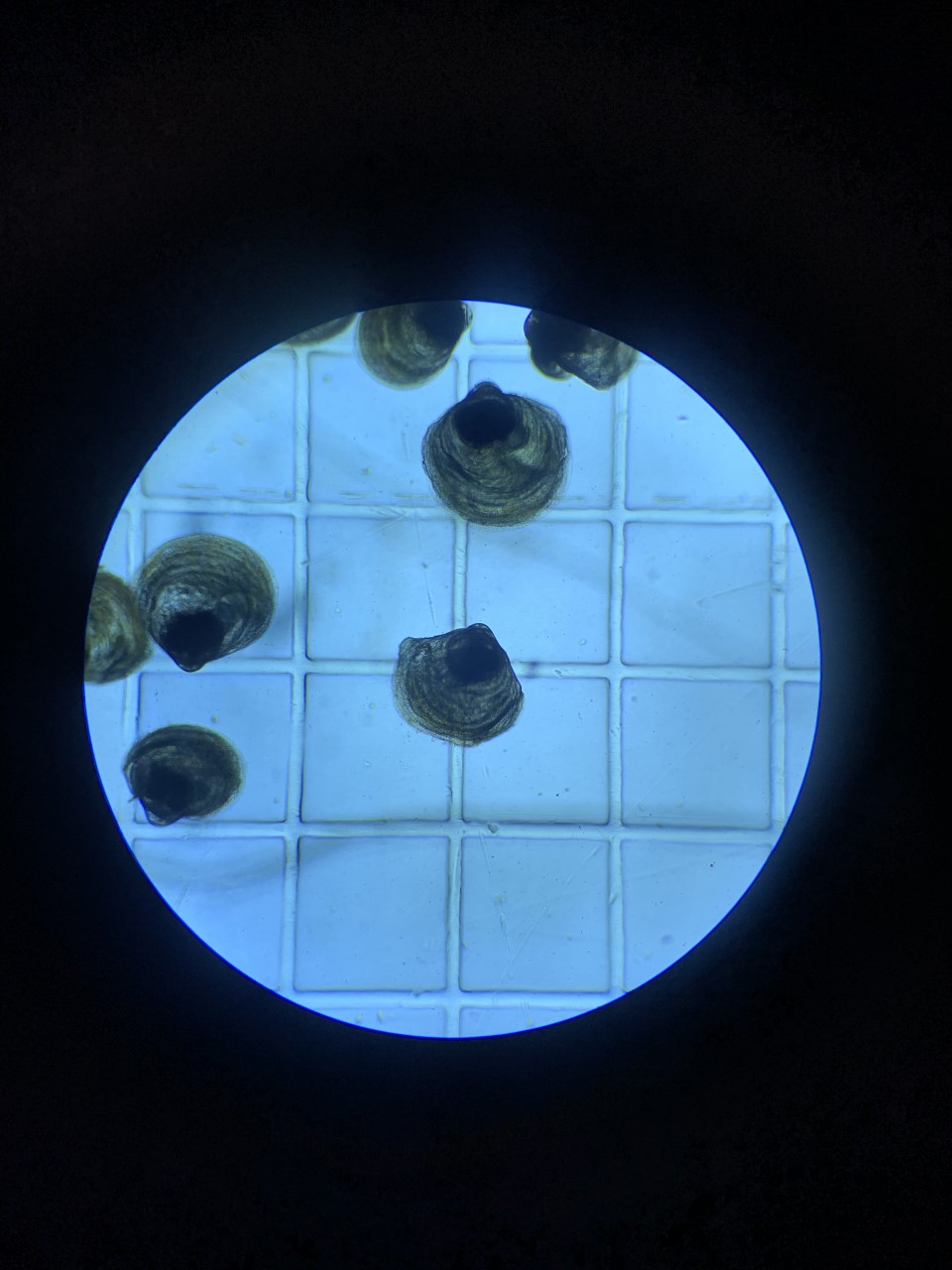

Throughout the festival lunch times I am inviting participants to encounter the clay and oyster shells, to respond to them and to make an art work with me. Students, staff and visitors can engage with the project through making, discussing, photographing and viewing. This event is specifically designed to provide the UNSW Community with the opportunity to engage in co creating a piece of eco-friendly art that honours the Baludarri, the Sydney Rock Oyster, its shell, its histories and its stories. Oysters filter and feed, and together we will filter negativity and feed inclusivity, positivity, integration and well-being.Through the reef I want to affirm the essential role the humble oyster plays in the health of our Sea Country and the well-being of our communities. Time on Country and nature-based play and encounter is an essential aspect of our well-being. Each oyster shell, like each human is unique and in this work each person’s contribution is valued and equal. The clay will sun dry and harden over the five days in an emerging and organic way.

Working with clay can be mediative, it can heal. Art making can lift the spirits and engage the heart in healing and this work is enacted Reconciliation practise where the UNSW Festival community has the opportunity to come together and co create an oyster reef; a reef of hope, a bed of support for each other and our mother earth.

Together, we will build positive ecosystems and manifestations of a healthy community.

I invited UNSW Diversity Festival Director Fergus Grealy into the studio this week to share his festival vision.

Fergus told me that Diversity Fest was week-long celebration at UNSW Sydney from 23 – 27 September 2019 which aims to bring students and staff together to embrace the diversity of the UNSW community and ignite broader conversations on creating an inclusive society, where everyone can participate. He said ‘There will be over 20 events held on campus during the week, including panel discussions, film screenings, concerts, art exhibitions and social gatherings. The events program will highlight the intersectionality of our diverse groups and have a greater emphasis on creating participatory experiences.’

Fergus and I connected over our shared love of creativities and transformations and sat on the blanket art works that I have been preparing for participants to sit on and during the art making on the Quad lawn. As we talked, we moulded clay and began the oyster shell and spat dialogues. Together, we seeded the work and we spoke about the project inclusion into the festival and its deep and embedded approach to fostering health and well being through shared purpose. Hands on, hands with, the human print marks the clay and the shell provides the safe harbour for ideas to grow.

During our studio based conversation and art making, Fergus explained to me ‘It is for these reasons that The Baludarri Bed Making Project has been included in Diversity Fest; the project is primarily informed by Indigenous knowledge and practice, but it also touches on environmental issues, mental well-being and it might even reveal the gender non-conformity of the oyster for a portion of their lifecycle. The project will be formed by community participation and the process will organically allow for this transference of knowledge.’